Let’s return now to a bit more music theory as we establish a working vocabulary and an understanding of musical notation.

[wpfilebase tag=file id=32 tpl=supplement /]

A scale is an ordered set of musical notes that are defined relative to a fundamental frequency, also known as the tonal center or tonic. There are different types of scales defined in music, which vary in the number of notes played and the intervals between the notes.

Table 3.1 lists seven types of scales divided into three general categories – chromatic, diatonic, and pentatonic. A list of 1s and 2s is a convenient way to represent the semitone intervals between each note in a scale. Moving by a semitone is represented by the number 1, meaning “move over a semitone from the previous note.” Moving by a whole tone is represented by the number 2, meaning “move over two semitones from the previous note.”

A chromatic scale consists of 12 notes. (However, when the scale is played, usually the 13th note is played, which is one octave above the first note. This note is note counted as one in the scale because it is the same note as the first one, but one octave above.) A chromatic scale starts on any pitch, and then each note is separated from the previous one by a semitone. Thus the pattern of a chromatic scale (where the 13th note is played) is represented simply by the list [1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1]. Note that while 13 notes are played, there are only 12 numbers on the list. The first note is played, and then the list represents how many semitones to move over to play the following notes.

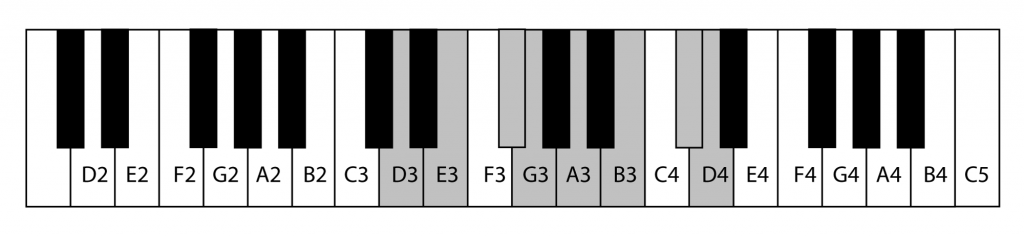

A diatonic scale has seven notes. In a major diatonic scale, the pattern is [2 2 1 2 2 2 1], assuming again that one more note is added as the scale is played, ending the scale one octave above where it began. This means, “start on the first note, move over by a tone, a tone, a semitone, a tone, a tone, a tone, and a semitone.” A major diatonic scale beginning on D3 (and adding an extra note) is depicted in Figure 3.8. Those who grow up in the tradition of Western music become accustomed to the sequence of sounds in a diatonic scale as the familiar “do re mi fa so la ti do.” A diatonic scale can start on any note, but all diatonic scales have the same pattern of sound in them; one scale is just higher or lower than another. Diatonic scales sound the same because the differences in the frequencies between consecutive notes on the scale follow the same pattern, regardless of the note you start on.

A minor diatonic scale is played in the pattern [2 1 2 2 1 2 2]. This pattern is also referred to as the natural minor. There are variations of minor scales as well. The harmonic minor scale follows the pattern [2 1 2 2 1 3 1], where 3 indicates a step and a half. The melodic minor follows the pattern [2 1 2 2 2 2 1] in the ascending scale, and [2 2 1 2 2 1 2] in the descending scale (played from highest to lowest note). The pattern of whole and half steps for major and minor scales are given in Table 3.1.

[table caption=”Table 3.1 Pattern of whole and half steps for various scales” width=”80%” colalign=”center|center”]

Type of scale,Pattern of whole steps (2) and half steps (1)

chromatic,1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

major diatonic,2 2 1 2 2 2 1

natural minor diatonic,2 1 2 2 1 2 2

harmonic minor diatonic,2 1 2 2 1 3 1

melodic minor diatonic,2 1 2 2 2 2 1 ascending~~2 2 1 2 2 1 2 descending

pentatonic major,2 3 2 2 3 or 2 2 3 2 3

pentatonic minor,3 2 3 2 2 or 3 2 2 3 2

[/table]

Two final scale types ought to be mentioned because of their prevalence in music of many different cultures. These are the pentatonic scales, created from just five notes. An example of a pentatonic major scale results from playing only black notes beginning with F#. This is the interval pattern 2 2 3 2 3, which yields the scale F#, G#, A#, C#, D#, F#. If you play these notes, you might recognize them as the opening strain from “My Girl” by the Temptations, a pop song from the 1960s. Another variant of the pentatonic scale has the interval pattern 2 3 2 2 3, as in the notes C D F G A C. These notes are the ones used in the song “Ol’ Man River” from the musical Showboat (Figure 3.9).

[table caption=”Figure 3.9 Pentatonic scale used in “Ol Man River”” th=”0″ width=”250px”]

“Ol’ man river,”

C C D F

Dat ol’ man river

D C C D F

He mus’know sumpin’

G A A G F

“But don’t say nuthin’,”

G A C D C

He jes’keeps rollin’

D C C A G

He keeps on rollin’ along.

A C C A G A F

[/table]

To create a minor pentatonic scale from a major one, begin three semitones lower than the major scale and play the same notes. Thus, the pentatonic minor scale relative to F#, G#, A#, C#, D#, F# would be D#, F#, G#, A#, C#, D#, which is a D# pentatonic minor scale. The minor relative to C D F G A C would be A C D F G A, which is an A pentatonic minor scale. As with diatonic scales, pentatonic scales can be set in different keys.

It’s significant that a chromatic scale really has no variation in the sequence of notes played. We simply move up by semitone steps of [1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1]. The distance between neighboring notes is always the same. In a diatonic scale, on the other hand, there is a pattern of varying half steps and whole steps between notes. The pattern gives notes different importance to the ear relative to the key, also called the tonic. This difference in the roles that notes play in a diatonic scale is captured in the names given to these notes, listed in Table 3.2. Roman numerals are conventionally used for the positions of these notes. These names will become more significant when we discuss chords later in this chapter.

[table caption=”Table 3.2 Technical names for notes on a diatonic scale” width=”250px” colalign=”center|center”]

Position,Name for note

I,tonic

II,supertonic

III,mediant

IV,subdominant

V,dominant

VI,submediant

VII,leading note

[/table]