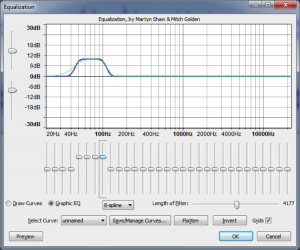

A graphic equalizer is one of the most basic types of EQ. It consists of a number of fixed, individual frequency bands spread out across the audible spectrum, with the ability to adjust the amplitudes of these bands up or down. To match our non-linear perception of sound, the center frequencies of the bands are spaced logarithmically. A graphic EQ is shown in Figure 7.3. This equalizer has 31 frequency bands, with center frequencies at 20 Hz, 25, Hz, 31 Hz, 40 Hz, 50 Hz, 63 Hz, 80 Hz, and so forth in a logarithmic progression up to 20 kHz. Each of these bands can be raised or lowered in amplitude individually to achieve an overall EQ shape.

While graphic equalizers are fairly simple to understand, they are not very efficient to use since they often require that you manipulate several controls to accomplish a single EQ effect. In an analog graphic EQ, each slider represents a separate filter circuit that also introduces noise and manipulates phase independently of the other filters. These problems have given graphic equalizers a reputation for being noisy and rather messy in their phase response. The interface for a graphic EQ can also be misleading because it gives the impression that you’re being more precise in your frequency processing than you actually are. That single slider for 1000 Hz can affect anywhere from one third of an octave to a full octave of frequencies around the center frequency itself, and consequently each actual filter overlaps neighboring ones in the range of frequencies it affects. In short, graphic EQs are generally not preferred by experienced professionals.