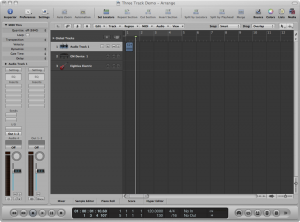

A software MIDI sequencer serves as an interface between the input and output. A track is an editable area on your sequencer interface. You can have dozens or even hundreds of tracks in your sequencer. Tracks are associated with areas in memory where data is stored. In a multitrack editor, you can edit multiple tracks separately, indicating input, output, amplitude, special effects, and so forth separately for each. Some sequencers accommodate three types of tracks: audio, MIDI, and instrument. An audio track is a place to record and edit digital audio. A MIDI track stores MIDI data and is output to a synthesizer, either a software device or to an external hardware synth through the MIDI output ports. An instrument track is essentially a MIDI track combined with an internal soft synth, which in turn sends its output to the sound card. It may seem like there isn’t much difference between a MIDI track and an instrument track. The main difference is that the MIDI track has to be more explicitly linked to a hardware or software synthesizer that produces its sound, whereas an instrument track has the synth, in a sense, “embedded” in it. Figure 6.12 shows each of these types of tracks.

A channel is a communication path. According to the MIDI standard, a single MIDI cable can transmit up to 16 channels. Without knowing the details of how this is engineered, you can just think of it abstractly as 16 separate lines of communication.

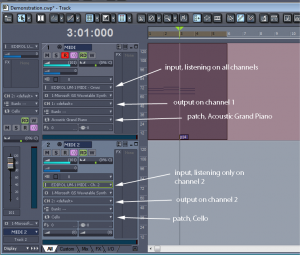

There are both input and output channels. An incoming message can tell what channel it is to be transmitted on, and this can route the message to a particular device. In the sequencer pictured in Figure 6.13, track 1 is listening on all channels, indicated by the word OMNI. Track 2 is listening only on Channel 2.

The output channels are pointed out in the figure, also. When the message is sent out to the synthesizer, different channels can correspond to different instrument sounds. The parameter setting marked with a patch cord icon is the patch. A patch is a message to the synthesizer – just a number that indicates how the synthesizer is to operate as it creates sounds. The synthesizer can be programmed in different ways to respond to the patch setting. Sometimes the patch refers to a setting you’ve stored in the synthesizer that tells it what kinds of waveforms to combine or what kind of special effects to apply. In the example shown in Figure 6.13, however, the patch is simply interpreted as the choice of instrument that the user has chosen for the track. Track 1 is outputting on Channel 1 with the patch set to Acoustic Grand Piano. Track 2 is outputting on Channel 2 with the patch set to Cello.

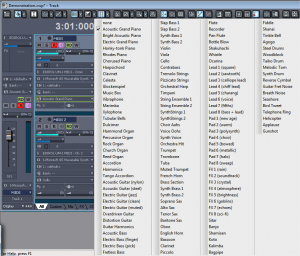

It’s possible to call for a patch change by means of the Program Change MIDI message. This message sends a number to the synthesizer corresponding to the index of the patch to load. A Program Change message is inserted into track 1 in Figure 6.13. You can see a little box with p14 in it at the bottom of the track indicating that the synth should be changed to patch 14 at that point in time. This is interpreted as changing the instrument patch from a piano to tubular bells. In the setup pictured, we’re just using the Microsoft GS Wavetable Synth as opposed to a more refined synth. For the computer’s built-in synth, the patch number is interpreted according to the General MIDI standard. The choices of patches in this standard can be seen when you click on the drop down arrow on the patch parameter, as shown in Figure 6.14. You can see that the fifteenth patch down the list is tubular bells. (The Program Change message is still 14 because the numbering starts at 0.)

In a later section in this chapter, we’ll look at other ways that the Program Change message can be interpreted by a synthesizer.